> Continuous Improvement Articles

Sometimes People ARE the Problem

I see a lot of talk in Lean circles about blaming the process and not the person.

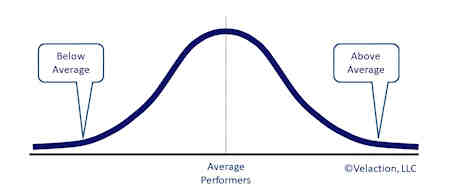

The truth is, people fall on a spectrum for most skills and characteristics. I’m not sure if it is a bell curve or some other distribution, but with nearly all traits and skills, there is a pretty large cluster of people in the middle, and then some outliers on both the really good side, and the really bad side.

The question at hand is where the spec limit for the job falls versus that curve.

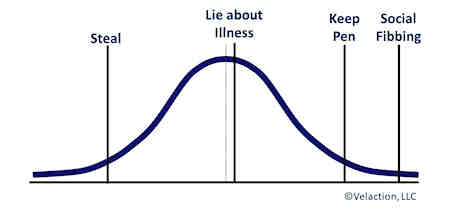

Take honesty, for example. Most people are fairly honest. I’ve seen a lot OF instances where a person drops something—maybe money, or a wallet, or a phone, and several people all rush to return it. Now I know that there are people who will try to take the wallet. I’m just happy that I’ve seen far more of the former in my life than the latter.

But even the best of people will fib on occasion. They may lie about being sick to take a day off, or they might lie to their school about a child being ill, so they can catch an earlier flight on a long weekend. They tell Aunt Ester that dinner tasted great, when it really wasn’t so hot—both figuratively, and literally. Or they end up with a pen from work in their car.

When you compare the how the honesty curve fits relative to the limit line for your job requirements, you’ll find that it gets drawn pretty far out on the curve—out in the area where thievery occurs, and it isn’t just a pen, but a full case of office supplies.

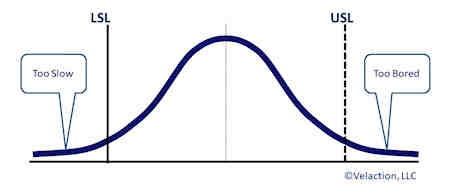

The same holds true for skills, but with them, the line tends to cut into the curve a lot more. Let’s look at the speed for processes. How quickly a person can line up a bolt into a hole, for example, also falls on a curve.

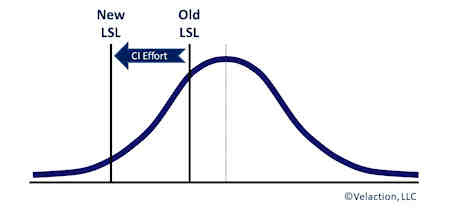

Here’s where continuous improvement efforts really help, and why you should not immediately blame the person.

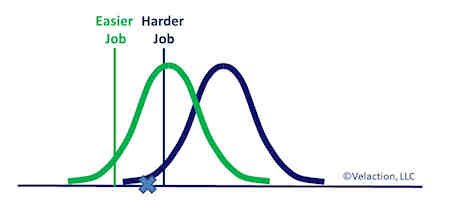

Lean lets you keep the spec limit well outside of the mass of people in the middle. With a good work design, you should be able to set your processes up so most people can keep up at a reasonable pace. Poor processes require extraordinary human effort. Good processes are easy to do.

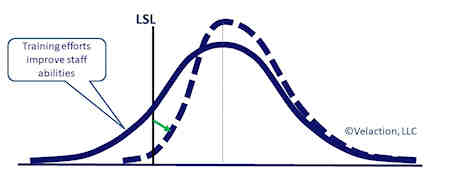

With good training, you can pinch the curve a lot narrower, and help more people get into that area where the pace of work is not too fast for them. Now, this is not a typical improvement pattern, because we really are not trying to narrow the curve. We don’t want to reduce performance at the high end. What we are actually doing is skewing the curve.

But, if you know anything about bell curves, it’s really hard to get that whole tail to fit inside the spec limit. It’s not just that it is hard to do. You sometimes don’t want to do it.

If you relax the requirements too much, so nearly everyone can do a job, most people are going to be really bored because the pace is too slow for them. They’ll hate the job.

And that that gets me back to the original point.

There are a lot of people that I am glad are not flying my plane, or operating on me, or managing the money at my bank, or running the cooling tower at the reactor. No matter how good the processes are, some people will find a way to prove to us that the processes were maybe not that great after all. Some processes require special skills, intelligence, and characteristics.

Now, to be sure, more of the people curve at your company probably fits into the spec limits at your job than at the nuclear plant or in the operating room. But you will still have some cutoff at the end of the tail. It won’t be as catastrophic as any of the really demanding jobs I mentioned, but it will be frustrating for leaders, for coworkers, and for the person in the wrong job.

They won’t be able to keep up, so will need extra help. They’ll have low morale. They will probably try to compensate and will end up making mistakes.

So when people say, blame the process, not the person, in most cases it holds true. The first effort should be to improve the process so the spec limit is way far down the tail of the performance bell curve. The second effort should be training.

But when both of those things have been done, on occasion, you still end up with a person who simply can’t do the work. It becomes time to blame the person. Now don’t get up in arms. I’m not really saying to get confrontational and actually blame the person. What I am saying is that it becomes time to make a change.

The person is in the wrong job. They can’t do the work.

Best case is that you are able to find an alternate job that is less demanding. Worst case is that the person should be let go. Follow your policies on this, of course, but leaders need to make hard decisions sometimes, and as a last resort, sometimes that decision is to fire someone.

Now, why did I write this article? What’s my point? In a nutshell, I want you to have a realistic expectation for what continuous improvement can do for you. It’s not a cure all. It takes hard work, and effort, and sometimes, yes, tough actions to make it work.

The upside, though, is that this is uncommon. Normally, just the effort to improve processes and train people improves things markedly. People are happiest when their work is a bit challenging, but not overly taxing. Trimming off the end of the tail holding things back for the rest of your team, hard as it is, helps a lot of people.

0 Comments